1.1 Strategic Management

The analyses, decisions, and actions an organization undertakes in order to create and sustain competitive advantages. The essence of strategic management is the study of why some firms outperform others: strategy is all about being different from everyone else.

The four key attributes of Strategic Management are:

1) It is directed toward overall organizational goals and objectives;

2) It includes multiple stakeholders in decision making;

3) It requires incorporating both short-term and long-term perspectives;

4) It involves the recognition of trade-offs between effectiveness and efficiency.

Stakeholders

Individuals, groups, and organizations who have a stake in the success of the organization, including owners (shareholders in a publicly held corporation), employees, customers, suppliers, and the community at large.

Stakeholder Group Nature of claim

Stakeholder Group | Nature of claim |

Stockholders Employees Suppliers Creditors Customers Government Communities | dividends, capital appreciation; wages, benefits, safe working environment; payment on time, assurance of continued relationship; payment of interest, repayment of principal; value, warranties; taxes, compliance with regulations; good citizenship behavior such as charities, employment, not polluting the environment. |

Effectiveness

Tailoring actions to the need of an organization rather than wasting effort, or “doing the right thing.”

Efficiency

Performing actions at a low cost relative to a benchmark, or “doing things right.”

Operational Effectiveness

Performing similar activities better than rivals.

Ambidexterity

The challenge mangers face of both aligning resources to take advantage of existing product markets as well as proactively exploring new opportunities.

1.2 The Strategic Management Process

Three ongoing processes that are central to strategic management are analyses, decisions and actions. These three processes, referred to as strategy analysis, formulation and implementation, are highly interdependent.

An alternative model of strategy development:

- Intended strategy: strategy in which organizational decisions are determined only by analysis.

- Realized strategy: strategy in which organizational decisions are determined by both analysis and unforeseen environmental developments, unanticipated resource constraints, and/or changes in managerial preferences.

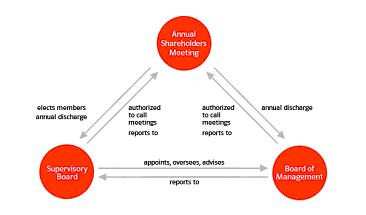

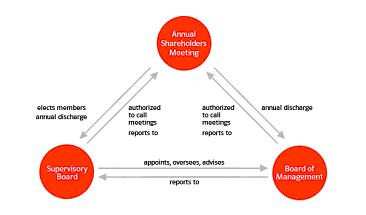

1.3 The Role of Corporate Governance and Stakeholder Management Corporate Governance

The relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of corporations. The primary participants are:

1) the shareholders;

2) the management (led by the chief executive officer);

3) the board of directors.Generating long-term returns for the shareholders is the primary goal of a publicly held corporation.

There are two opposing ways of looking at the role of stakeholder management in the strategic management process:

1) Zero sum: the role of management is to look upon the various stakeholders as competing for the organization’s resources. In essence, the gain of one individual or group is the loss of another individual or group.

2) Stakeholder symbiosis: stakeholders are dependent upon each other for their success and well-being. That is, managers acknowledge the interdependence among employees, suppliers, customers, shareholders and the community at large.

Social responsibility

The expectation that businesses or individuals will strive to improve the overall welfare of society.

Triple Bottom Line

The assessment of a company’s performance in financial, social and environmental dimensions.

1.4 The Strategic Management Perspective: An Imperative throughout the Organization

To develop and mobilize people and other assets, leaders are needed throughout the organization. Everyone must be involved in the stratgic management process. There is a critical need for three types of leaders:

1) Local line leaders who have significant profit-and-loss responsibility;

2) Executive leaders who champion and guide ideas, create a learning infrastructure and establish a domain for taking action;

3) Internal networkers who, although they have little positional power and formal authority, generate their power through the convinction and clarity of their ideas.

Top-level executives are key in setting the tone for the empowerment of employees.

There are two perspectives of leadership:

1) Romantic view of leadership: situations in which the leader is the key force determining the

organization’s success – or lack thereof.

2) External view of leadership: situations in which external forces – where the leader has limited influence - determine the organization’s success.

1.5 Ensuring Coherence in Strategic Direction

Hierarchy of goals

Organizational goals ranging from, at the top, those that are less specific yet able to evoke powerful and compelling mental images, to, at the bottom, those that are more specific and measurable.

Vision

Organizational goal(s) that evoke(s) powerful and compelling mental images.

Mission Statement

A set of organizational goals that include both the purpose of the organization, its scope of operations, and the basis of its competitive advantage.

Strategic Objectives

A set of organizational goals that are used to operationalize the mission statement and that are specific and cover a well-defined time frame. They must be measurable, specific, appropriate, realistic and timely.

2.1 Three important processes to develop forecasts:

1) Environmental Scanning: surveillance of a firm’s external environment to predict environmental changes and detect changes already under way.

2) Environmental Monitoring: a firm’s analysis of the external environment that tracks the evolution of environmental trends, sequence of events, or streams of activities.

3) Competitive Intelligence: a firm’s activities of collecting and interpreting data on competitors, defining and understanding the industry, and identifying competitors’ strengths and weaknesses.

Environmental Forecasting

The development of plausible projections about the direction, scope, speed, and intensity of environmental change. A danger of forecasting is that managers may view uncertainty as black and white and ignore important grey areas.

Scenario Analysis

An in-depth approach to environmental forecasting that involves experts’ detailed assessments of societal trends, economics, politics, technology, or other dimensions of the external environment.

SWOT Analysis

A framework for analyzing a company’s internal and external environment and that stands for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

The strengths and weaknesses portion of SWOT refers to the internal conditions of the firm. opportunities and threats are environmental conditions external to the firm.

Limitations of SWOT Analysis

By listing the firm’s attributes, managers have the raw material needed to perform more in-depth strategic analysis. However, SWOT cannot show them how to achieve a competitive advantage, because of the following limitations:

- Strengths may not lead to an advantage;

- SWOT’s focus on the external environment is too narrow;

- SWOT gives a one-shot view of a moving target, because it is primarily a static assessment;

- SWOT overemphasizes a single dimension of strategy.

2.2 The General Environment

Factors external to an industry, and usually beyond a firm’s control, that affect a firm’s strategy. The general environment is divided into six segments:

1) Demographic: aging population, rising affluence, changes in ethnic composition, geographic

distribution of population etc;

2) Sociocultural: more women in the workforce, increase in temporary workers, greater concern for fitness, concern for environment etc;

3) Political/Legal: tort reform, Americans with Disabilities Act, taxation of local, state and federal levels, Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 etc;

4) Technological: genetic engineering, emergence of Internet technology, pollution/global warming, wireless communication etc;

5) Economic: interest rates, unemployment rates, consumer price index, trends in GDP, changes in stock market valuations etc;

6) Global: increasing global trade, currency exchange rates, emergence of the Indian and Chinese economies, creation of WTO etc.

2.3 The Competitive Environment

Factors that pertain to an industry and affect a firm’s strategies. The nature of competition in an industry as well as the profitability of a firm is often more directly influenced by developments in the competitive environment.

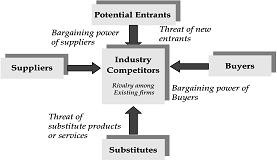

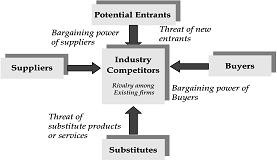

Porter’s Five-Forces Model

The “five-forces” model has been the most commonly used analytical tool for examining the competitive environment. It describes the competitive environment in terms of five basic competitive forces (see the figure):1) Potential Entrants;2) Buyers;3) Suppliers;4) Substitutes;5) Industry Competitors.

1) Threat of new entrants: possibility that the profits of established firms in the industry may be eroded by new competitors. There are six major sources of entry barriers:

- Economies of Scale;

- Product Differentiation;

- Capital Requirements;

- Switching Costs;

- Access to Distribution Channels;

- Cost Disadvantages Independent of Scale.

2) Bargaining Power of Buyers: buyers threaten an industry by forcing down prices, bargaining for higher quality or more services, and playing competitors against each other. A buyer group is powerful under the following circumstances:

- It is concentrated or purchases large volumes relative to seller sales;

- The products it purchases from the industry are standard or undifferentiated;

- The buyer faces few switching costs;

- The buyers pose a credible threat of backward integration;

- The industry’s product is unimportant to the quality of the buyer’s products or services.

3) Bargaining Power of Suppliers:

- The supplier group is dominated by a few companies and is more concentrated (few firms dominate the industry) than the industry it sells to;

- The supplier group is not obliged to contend with substitute products for sale to the industry;

- The industry is not an important customer of the supplier group;

- The supplier group’s products are differentiated or it has built up switching costs for the buyer;

- The supplier group poses a credible threat of forward integration.

4) Threat of Substitute Products and Services: all firms within an industry compete with industries producing substitute products and services. Substitutes limit the potential returns of an industry by placing a ceiling on prices that firms in that industry can profitably charge. The more attractive the price/performance ratio of substitute products, the tighter the lid on an industry’s profits.

5) Intensity of Rivalry among competitors in an Industry: rivalry among existing competitors takes the form of jockeying for position. Firms use tactics like price competition, advertising battles, product introductions, and increased customer service or warranties. Intense rivalry is the result of several interacting factors, including the following:

- Numerous or equally balanced competitors

- Slow industry growth

- High fixed or storage costs

- Lack of differentiation or switching costs

- Capacity augmented in large increments

- High exit barriers

Caveats of using industry analysis:

- Managers must not always avoid low profit industries (or low profit segments in profitable industries). Such industries can still yield high returns;

- the five-forces analysis implicitly assumes a zero-sum game, determining how a firm can enhance its position relative to the forces. Yet, such an approach can often be short-sighted;

- The five-forces analysis also has been criticized for being essentially a static analysis. External forces as well as strategies of individual firms are continually changing the structure of all industries.

Complements

Products or services that have an impact on the value of a firm’s products or services.

Strategic Groups

Clusters of firms that share similar strategies. Competition tends to be more intense among firms within a strategic group than between strategic groups.

One can derive an analytical tool from the strategic groups concept:

- Strategic groupings help a firm to identify barriers to mobility that protect a group from attacks by other groups;

- Strategic groupings help a firm identify groups whose competitive position may be marginal or tenuous;

- Strategic groupings help chart the future directions of firms’ strategies;

- Strategic groups are helpful in thinking through the implications of each industry trend for the strategic group as a whole.

While we believe SWOT analysis is very helpful as a starting point, it should not form the primary basis for evaluating a firm’s internal strenghts and weaknesses or the opportunities and threats in the environment. The value-chain analysis provides greater insights into analyzing a firm’s competitive position than SWOT analysis does by itself.

3.1 Value-Chain Analysis

A strategic analysis of an organization that uses value-creating activities

- Primary activities: inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, service;

- Support activities: infrastructure, human resources management, technology development, procurement.

Primary activities: sequential activities of the value chain that refer to the physical creation of the

product or service, its sale and transfer to the buyer, and its service after sale, including:

- Inbound Logistics: is primarily associated with receiving, storing and distributing inputs to the product. It includes material handling, warehousing, inventory control, vehicle scheduling, and returns to suppliers;

- Operations: include all activities associated with transforming inputs into the final product form, such as machining, packaging, assembly, testing printing, and facility operations;

- Outbound Logistics: is associated with collecting, storing, and distributing the product or service to buyers. These activities include finished goods, warehousing, material handling, delivery vehicle operation, order processing, and scheduling;

- Marketing and Sales: are associated with purchases of products and services by end users and the inducements used to get them to make purchases. They include advertising, promotion, sales force, channel selection, channel relations and pricing;

- Service: includes all actions associated with providing service to enhance or maintain the value of the product, such as installation, repair, training, parts supply, and product adjustment.

Support activities: Activities of the value chain that either add value by themselves or add value

through important relationships with both primary activities and other support activities; including:

- Procurement: refers to the function of purchasing inputs used in the firm’s value chain, not to the purchased inputs themselves. Purchased inputs include raw materials, supplies, and other consumable items as well as assets such as machinery, laboratory equipment, office equipment, and buildings;

- Technology Development: every value activity embodies technology. Technology development related to the product and its features supports the entire value chain, while other technology development is associated with particular primary or support activities;

- Human Resource Management: consists of activities involved in the recruiting, hiring, training, development, and compensation of all types of personnel. It supports both individual primary and support activities (e.g. hiring of engineers and scientists) and the entire value chain (e.g. negotiation with labor unions);

- Infrastructure (General Administration): consists of a number of activities, including general management, planning, finance, accounting, legal and government affairs, quality management, and Information systems. It typically supports the entire value chain and not individual activities.

There are two levels of interrelationships among value-chain activities:

1) Interrelationships among activities within the firm;

2) Interrelationships among activities within the firm and with other organizations (e.g. customers and suppliers) that are part of the firm’s expanded value chain.

3.2 Resource-Based View of the Firm

Perspective that firms’ competitive advantages are due to their endowment of strategic resources which are valuable, rare, costly to imitate, and costly to substitute. It combines two perspectives:

1) The internal analysis of phenomena within a company;

2) An external analysis of the industry and its competitive environment.

Sustainable Competitive Advantages

Resources alone are not a basis for competitive advantages, nor are advantages sustainable over time. In some case, a resource or capability helps a firm to increase its revenues or to lower costs but the firm derives only a temporary advantage because competitors quickly imitate or substitute it. For a resource to provide a firm with the potential for a sustainable competitive advantage, it must have four attributes:

1) It must be valuable: in the sense that it exploits opportunities and/or neutralizes threats in the firm’s environment by formulating and implementing strategies that improve its efficiency or effectiveness;

2) It must be rare: among the firm’s current and potential competitors;

3) It must be difficult to imitate: If a resource is inimitable, then any profits generated are more likely to be sustainable. Since an advantage based on inimitability won’t last forever, managers can forestall them and sustain profits for a while by developing strategies around resources that have at least one of the following four characteristics:

- Physical uniqueness: is by definition inherently to copy;

- Path dependency: a characteristic of resources that is developed and/or accumulated through a unique series of events;

- Casual ambiguity: a characteristic or a firm’s resources that is costly to imitate because a competitor cannot determine what the resource is and/or how it can be re-created;

- Social complexity: a characteristic of a firm’s resources that is costly to imitate because the social engineering required is beyond the capability of competitors, including interpersonal relations among managers, organizational culture, and reputation with suppliers and customers;

4) No substitutes readily available: the fourth requirement for a firm resource to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage is that there must be no strategically equivalent resources that are themselves not rare or inimitable.

Extending the Resource-Based View of the firm

Although the resource-based view of the firm has been useful in determining when firms will create competitive advantages and enjoy high levels of profitability, it has not been developed to address how a firm’s profits will be distributed to a firm’s management and employees. Four factors help explain the extent to which employees and managers will be able to obtain a proportionately high level of the profits that they generate:

1) Employee Bargaining Power: if employees are vital to forming a firm’s unique capability, they will earn disproportionately high wages;

2) Employee Replacement Cost: if employees’ skills are idiosyncratic and rare, they should have high bargaining power based on the high cost required by the firm to replace them;

3) Employee Exit Costs: this factor may tend to reduce an employee’s bargaining power, because an individual may face high personal costs when leaving the organization;

4) Manager Bargaining Power: managers’ power is usually based on how well they create resource-based advantages. Thus, managers may not know as much about the specific nature of customers and technologies, they are in a position to have a more thorough, integrated understanding of the total operation.

There are three types of firm resources:

1) Tangible Resources: organizational assets that are relatively easy to identify, including physical assets, financial resources, organizational resources, and technological resources;

2) Intangible Resources: organizational assets that are difficult to identify and account for and that are typically embedded in unique routines and practices, including human resources, innovation resources, and reputation resources;

3) Organizational Capabilities: the competences and skills that a firm employs to transform inputs into outputs.

3.3 Evaluating Firm Performance: Two approaches

1) Financial Ratio Analysis: Identifies how a firm is performing according to its balance sheet, income statement, and market valuation. The beginning point in analyzing the financial position of a firm is to compute and analyze five different types of financial ratios.

Short-term solvency or liquidity Long-term solvency measures Asset management (=turnover) Profitability Market value | current ratio, quick ratio, cash ratio; total debt ratio, debt-equity ratio, equity multiplier, times interest earned ratio, cash coverage ratio; inventory turnover, days’ sales in inventory, receivables turnover, total asset turnover; profit margin, return on asset (ROA), return on equity (ROE); price-earnings ratio, market-to-book-ratio. |

It is important to note that a meaningful ratio analysis must go beyond the calculation and interpretation of financial ratios. It must include an analysis of how ratios change over time as well as how they are interrelated. When evaluating a firm’s financial performance one should also compare it with industry norms. A firm’s profitability may appear impressive at first glance. However, it may pale when compared with industry standards or norms.

2) Balanced Scorecard: a method of evaluating a firm’s performance using performance measures from the customers’, internal, innovation and learning, and financial perspectives.

- Customer Perspective: how a company is performing from its customers’ perspective is a top priority for management. The balanced scorecard requires that managers translate their general mission statements on customer service into specific measures that reflect the factors that really matter to customers;

- Internal Perspective: although customer-based measures are important, they must be translated into indicators of what the firm must do internally to meet customers’ expectations;

- Innovation and Learning Perspective: given the rapid rate of markets, technologies, and global competition, the criteria for success are constantly changing. A firm’s ability to do well from a learning and growth perspective is more dependent on its intangible than tangible assets: Three categories are critically important: Human capital (skills, talent, and knowledge), information capital (information systems), and organization leadership (culture, leadership);

- Financial Perspective: measures of financial performance indicate whether the company’s strategy, implementation, and execution are indeed contributing to bottom-line improvement. Typical financial goals include shareholder value and growth.

Potential Downsides And Limitations:

- Lack of a clear strategy;

- Limited or ineffective executive sponsorship;

- Poor data on actual performance;

- Too much emphasis on financial measures rather than nonfinancial measures;

- Inappropriate links of scorecard measures to compensation;

- Inconsistent or inappropriate terminology.

Knowledge Economy

An economy where wealth is created through the effective management of knowledge workers instead of by the efficient control of physical and financial assets.

Intellectual Capital

The difference between the market value of the firm and the book value of the firm, including assets such as reputation, employee loyalty, and commitment, customer relationships, company values, brand names, and the experience and skills of employees.

Intellectual Capital = Market value of firm – Book Value of firm.

Human Capital

The individual capabilities, knowledge, skills, and experience of a company’s employees and

managers.

Social Capital

The Network of relationships that individuals have both inside and outside the organization.

Explicit knowledge

Knowledge that is codified, documented, easily reproduced, and widely distributed.

Tacit knowledge

Knowledge that is in the minds of employees and is based on their experiences and backgrounds.

Socially complex processes (leadership, culture and trust) play a central role in the creation of knowledge.

4.1 Human Capital: The Foundation of Intellectual Capital

All successful organizations must engage to build and leverage their human capital. Hiring is only the first of three key processes. Firms must also develop employees at all levels and specialties. Finally, the first two processes are for naught if firms can’t provide the working environment and intrinsic and extrinsic rewards to retain their best and brightest. These activities can be viewed as a “three-legged stool”, implying that it is difficult for firms to be successful if they ignore or are unsuccessful in any one of these activities.

Attracting Human Capital

The first step in the process of building superior human capital is input control: Attracting and selecting the right person. A popular phrase in this context is: “Hire for Attitude, Train for Skill”. Organizations are increasingly placing their emphasis on the general knowledge and experience, social skills, values, beliefs, and attitudes of employees. In particular, it is important to attract employees who can collaborate with others, give the importance of collective efforts such as teams and task forces.

Developing Human Capital

It is not enough to hire top-level talent and expect that the skills and capabilities of those employees remain current throughout the duration of their employment. Rather, training and devilment must take place at all levels of the organization. Three related topics are:

1) Encouraging Widespread Involvement;

2) Monitoring Progress and Tracking Development;

3) Evaluating Human Capital.

Retaining Human Capital

An organization can either try to force employees to stay in the firm or try to keep them from wanting to jump out by creating incentives. Some mechanisms for retaining human capital are:

- Employees’ identification with the organization’s mission and values;

- Providing challenging work and a stimulating environment;

- The importance of financial and nonfinancial rewards and incentives;

- Providing flexibility and amenities.

A key issue here is that a firm should not overemphasize financial rewards. After all, if individuals join an organization for money, they also are likely to leave for money. With money as the primary motivator, there is little chance that employees will develop firm-specific ties to keep them with the organization.

4.2 The Vital Role of Social Capital

Social capital refers to the network or relationships that individuals have throughout the organization as well as with customers and suppliers.

Social network analysis

Analysis of the pattern of social interactions among individuals.

Closure

The degree to which all members of a social network have relationships (or ties) with other groupmembers.

Bridging Relationships

Relationships in a social network that connect otherwise disconnected people.

Structural Holes

Social gaps between groups in a social network where there are few relationships bridging the groups.

Implications for Career Success

Clearly, effective social networks can provide many advantages for an organization. From an individual’s perspective, social networks deliver three unique advantages:

1) Private information: is gathered from personal contacts who can offer something unique that cannot be found in publicly available sources;

2) Access to Diverse Skill Sets: success is tied to the ability to transcend natural skill limitations through others;

3) Power: traditionally, a manager’s power was embedded in a firm’s hierarchy. But, when corporate organizations became flatter, that power was repositioned in the network’s brokers (people who bridged multiple networks), who could adapt to changes in the organization, develop clients, and synthesize opposing points of view.

The potential downside of Social Capital

These include the expenses that firms may bear when promoting social and working relationships among individuals as well as the potential for “groupthink”, wherein individuals are reluctant to express divergent (or opposing) views on an issue because of social pressures to conform.

Individuals may also use the contacts they develop to pursue their own interests and agendas that may be inconsistent with the organization’s goals and objectives.

4.3 Using Technology to Leverage Human Capital and Knowledge

Sharing knowledge and information throughout the organization can be a means of conserving resources, developing products and services, and creating new opportunities. There are relatively simple means of using technology, such as e-mail and networks where individuals can collaborate by way of personal computers.

Electronic Teams

Teams of individuals that complete tasks primarily through e-mail communication. These teams are

less restricted by the geographic constraints that are placed on face-to-face teams. Once formed, e-

teams can be more flexible in responding to unanticipated work challenges and opportunities.

Furthermore, e-teams can be very effective in generating “social capital” – the quality of relationships

and networks that leaders and team members form.

However, the geographical dispersion can also cause low cohesion, low trust among members, a lack of appropriate norms or standard operating procedures, or a lack of shared understanding among team members about their tasks.

Protecting the Intellectual Assets: Intellectual Property and Dynamic Capabilities

Although traditional approaches such as patents, copyrights, and trademarks are important, the development of dynamic capabilities may be the best protection in the long run.

Competitive advantage has a central role in the study of strategic management.

5.1 Three generic strategies

1) Overall Cost Leadership: a firm’s generic strategy based on appeal to the industry wide market using a competitive advantage based on low cost (experience curve). An overall low-cost position:

- Enables a firm to achieve above-average returns despite strong competition;

- Protects a firm against rivalry from competitors, because lower costs allow a firm to earn returns even if its competitors eroded their profits through intense rivalry;

- Provides more flexibility to cope with demands from powerful suppliers for input cost increase;

- Puts the firm in a favorable position with respect to substitute products introduced by new and existing competitors.

Potential pitfalls of overall cost leadership strategy include:

- Too much focus on one or a few value-chain activities;

- All rivals share a common input or raw material;

- The strategy is imitated too easily;

- A lack of parity on differentiation;

- Erosion of cost advantages when the pricing information available to customers increases.

Competitive Parity

A firm’s achievement of similarity, or being “on par”, with competitors with respect to low cost, differentiation, or other strategic product characteristic.

2) Differentiation Strategy: a firm’s generic strategy based on creating differences in the firm’s product or service offering by creating something that is perceived industry wide as unique and valued by customers. A differentiation strategy:

- Provides protection against rivalry since brand loyalty lowers customer sensitivity to price and raises customer switching costs;

- Avoids the need for a low-cost position, by increasing a firm’s margins;

- Provides higher margins that enable a firm to deal with supplier power;

- Reduces buyer power, because buyers lack comparable alternatives and are therefore less price sensitive;

- Enhances customer loyalty, thus reducing the threat of substitutes.

Potential pitfalls of differentiation strategy include:

- Uniqueness that is not valuable;

- Too much differentiation;

- Too high a price premium;

- Differentiation that is easily imitated;

- Dilution of brand identification through product-line extensions;

- Perceptions of differentiation may vary between buyers and sellers.

3) Focus Strategy: a firm’s generic strategy based on appeal to a narrow market segment within an industry. It requires that a firm either has a low-cost position with its strategic target, high

differentiation, or both. It is used to select niches that are least vulnerable to substitutes or

where competitors are weakest.

Potential pitfalls of focus strategy include:

- Erosion of cost advantages within the narrow segment;

- Even product and service offerings that are highly focused are subject to competition from new entrants and from imitation;

- Focusers can become too focused to satisfy buyer needs.

Combination Strategies: Integrating Overall Low Cost and Differentiation

According to study of nearly 1,800 strategic business units, the highest performers were businesses that attained both cost and differentiation advantages, followed by those that had either one or the other. Perhaps the primary benefit to firms that integrate low-cost and differentiation strategies is that it is generally harder for rivals to duplicate or imitate, because the strategy enables a firm to provide two types of value to customers: differentiated attributes (e.g. high quality, brand identification, reputation) and lower prices (because of the firm’s lower costs in value-creating activities).

Potential Pitfalls of Integrated Overall Cost Leadership and Differentiation Strategies:

- Firms that fail to attain both strategies may end up with neither and become “stuck in the middle”;

- Underestimating the challenges and expenses associated with coordinating value-creating activities in the extended value chain;

- Miscalculating sources of revenue and profit pools in the firm’s industry.

5.2 How the Internet and Digital Technologies are affecting the competitive strategies

a. Internet-Enabled Low-Cost Leader Strategies

- Online bidding and order processing are eliminating the need for sales calls and are minimizing sales force expenses;

- Online purchase orders are making many transactions paperless, thus reducing the cost of procurement and paper;

- Direct access to progress reports and the ability for customers to periodically check work in progress is minimizing rework;

- Collaborative design efforts using Internet technologies that link designers, materials, suppliers, and manufacturers are reducing the costs and speeding the process of new product development.

Potential Internet-Related Pitfalls for Low-Cost Leaders:

- One of the biggest threats to low-cost leaders is imitation (most software driven capabilities can be duplicated quickly and without threat of infringement or proprietary information);

- Companies than become overly enamored with suing the Internet for cost-cutting might suffer if they place too much attention on one business activity and ignore others.

b. Internet Enabled Differentiation Strategies:

- Personalized online access provides customers with their own “site within a site” in which their prior orders, status of current orders, and requests for future orders are processed directly on the supplier’s website;

- Online access to real-time sales and service information is being used to empower the sales force and continually update R&D and technology development efforts;

- Internet-based knowledge management systems that link all parts of the organization are shortening response times and accelerating organization learning;

- Quick online responses to service requests and rapid feedback to customer surveys and product promotions are enhancing marketing efforts.

Potential Internet-Related Pitfalls for Differentiators:

- Since Internet-enabled capabilities such as the ability to compare product features side-by-side or bid online for competing services, become part of the mainstream, it will become harder to use the Web to differentiate.

c. Internet-Enable Focus Strategies:

- Permission marketing techniques are focusing sales efforts on specific customers who opt to receive advertising notices;

- Niche portals that target specific groups are providing advertisers with access to viewers with specialized interests;

- Virtual organizing and online “officing” are being used to minimize firm infrastructure requirements;

- Procurement technologies that use Internet software to match buzzers and sellers are highlighting specialized buyers and drawing attention to smaller suppliers.

Potential Internet-Related Pitfalls for Focusers:

- A key danger for focusers using the Internet relates to correctly assessing the size of the online marketplace.

5.3 Industry Life Cycle Stages: Strategic Implications

Industry Life Cycle

The stages of introduction, growth, maturity, and decline that typically occur over the life of an

Industry:

1) Introduction Stage: the first stage of the industry life cycle characterized by (1) new products that are not known to customers, (2) poorly defined market segments, (3) unspecified product features, (4) low sales growth, (5) rapid technological change, (6) operating losses, and (7) a need for financial support;

2) Growth Stage: the second stage of the product life cycle characterized by (1) strong increases in sales; (2) growing competition; (3) developing brand recognition; and (4) a need for financing complementary value-chain activities such as marketing, sales, customer service, and research and development;

3) Maturity Stage: the third stage of the product life cycle characterized by (1) slowing demand growth, (2) saturated markets, (3) direct competition, (4) price competition, and (5) strategic emphasis on efficient operations. Firms are able to rescue products floundering in the maturity phase of their life cycles and return them to the growth phase by:

- Reverse Positioning: a break in industry tendency to continuously augment products, characteristic of the product life cycle, by offering products with fewer product attributes and lower prices;

- Breakaway Positioning: a break in industry tendency to incrementally improve products along specific dimensions, characteristic of the product life cycle, by offering products that are still in the industry but that are perceived by customers as being different;

4) Decline stage: the fourth stage of the product life cycle characterized by (1) falling sales and profits, (2) increasing price competition, and (3) industry consolidation. Four basic strategies are available in the decline phase:

- Maintaining: refers to keeping a product going without significantly reducing marketing support, technological development, or other investments, in the hope that competitors will eventually exit the market;

- Harvesting: involves obtaining as much profit as possible and requires that costs be reduced quickly;

- Exiting the market: involves dropping the product from a firm’s portfolio. Since a residual core of consumers may still use the product, eliminating it should be considered carefully;

- Consolidation: involves one firm acquiring at a reasonable price the best of the surviving firms in an industry. This enables firms too enhance market power and acquire valuable assets.

Turnaround Strategies

A strategy that reverses a firm’s decline in performance and returns it to growth and profitability:

1) Asset and cost surgery: firms in turnaround situations try to aggressively cut administrative expenses and inventories and speed up collection of receivables;

2) Selective product and market pruning: one strategy is to discontinue only marginally profitable product lines and focus all resources on a few core profitable areas;

3) Piecemeal productivity improvements: there are hundreds of ways in which a firm can eliminate costs and improve productivity. Although individually these are small gains, they cumulate over a period of time to substantial gains.

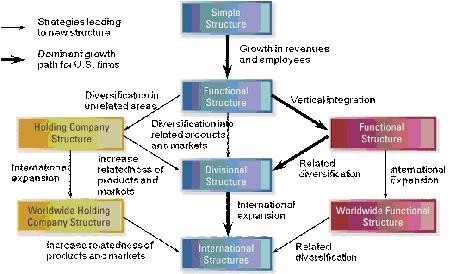

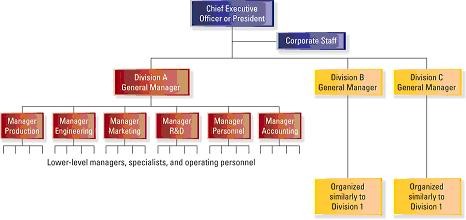

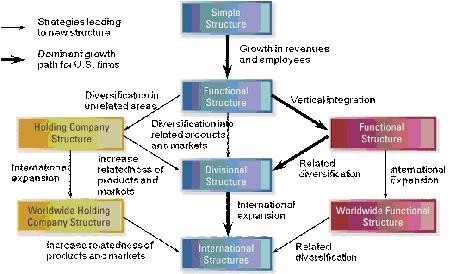

Why do some diversification efforts pay off and others produce disappointing results? Diversification initiatives – whether through mergers and acquisitions, strategic alliances and joint ventures, or internal development – must be justified by the creation of value for shareholders.

Given the seemingly high inherent downside risks and uncertainties, it might be reasonable to ask why companies should even bother with diversification initiatives. The answer, in a word, is synergy. This can have two different, but not mutually exclusive, meanings:

1) First, a firm may diversify into related businesses. Here, the primary potential benefits to be derived come from horizontal relationships;

2) Second, a corporation may diversify into unrelated businesses. In these instances, the primary potential benefits are derived largely from hierarchical relationships.

6.1 Related Diversification: Economies of Scope, Revenue Enhancement and Market Power

A firm entering a different business in which it can benefit from economies of scope, revenue enhancement and market power.

1) Economies of Scope: cost savings from leveraging core competencies or sharing related activities among businesses in a corporation:

- Core competencies: a firm’s strategic resources that reflect the collective learning in the organization. For a core competence to create value and provide a viable basis for synergy among the businesses in a corporation, it must meet three criteria:

i. The core competence must enhance competitive advantage(s) by creating superior customer value;

ii. Different businesses in the corporation must be similar in at least one important way related to the core competence;

iii. The core competencies must be difficult for competitor to imitate or find substitutes for;

- Sharing activities: having activities of two or more businesses’ value chains done by one of the businesses. Sharing activities can potentially provide two primary payoffs:

i. Cost savings: come from many sources, including elimination of jobs, facilities, and related expenses that are no longer needed when functions are consolidated, or from economies of scale in purchasing;

ii. Revenue enhancements: often an acquiring firm and its target may achieve a higher level of sales growth together than either company could on its own. Firms also can enhance the effectiveness of their differentiation strategies by means of sharing activities among business units.

2) Related Diversification (Market Power): firms’ abilities to profit through restricting or controlling supply to a market or coordination with other firms to reduce investment. Two principal means by which firms achieve synergy through market power are pooled negotiating power and vertical integration:

- Pooled negotiating Power: similar businesses working together or the affiliation of a business with a strong parent can strengthen an organization’s bargaining position relative to suppliers and customers and enhance its position vis-à-vis competitors. However, managers must carefully evaluate how the combined businesses may affect relationships with actual and potential customers, suppliers, and competitors;

- Vertical integration: an expansion or extension of the firm by integrating preceding or successive production processes. Although vertical integration is a means for an organization to reduce its dependence on suppliers or its channels of distribution to end users, it represents a major decision that an organization must carefully consider:

Benefits of vertical integration: | Risks of vertical integration: |

A secure source of raw materials or distribution channels; Protection of and control over valuable assets; Access to new business opportunities; Simplified procurement and administrative procedures.Loss of flexibility resulting from large investments; | Costs and expenses associated with increased overhead and capital expenditures; Problems associated with unbalanced capacities along the value chain; Additional administrative costs associated with managing a more complex set of activities. |

In making vertical integration decisions, 6 issues should be considered:

1) Is the company satisfied with the quality of the value that its present suppliers and distributors are providing?

2) Are there activities in the industry value chain presently being outsourced or performed independently by other that are a viable source of future profits?

3) Is there a high level of stability in the demand for the organization’s products?

4) How high is the proportion of additional production capacity actually absorbed by existing products or by the prospect of new and similar products?

5) Does the company have the necessary competencies to execute the vertical integration strategies?

6) Will the vertical integration initiative have potential negative impacts on the firm’s stakeholders?

Transaction cost perspective

A perspective that the choice of a transaction’s governance structure, such as vertical integration or market transaction, is influenced by transaction costs, including search, negotiating, contracting, monitoring, and enforcement costs, associated with each choice.

Vertical integration gives rise to a different set of costs: administrative costs. Coordinating different stages of the value chain now internalized with the firm causes administrative costs to go up. Therefore, decisions about vertical integration have to be based on a comparison of transaction costs and administrative costs.

6.2 Unrelated Diversification: Financial Synergies and Parenting

With unrelated diversification, unlike related diversification, few benefits are derived from horizontal relationships. Instead, potential benefits can be gained from vertical (or hierarchical) relationships.

Parenting advantage

The positive contributions of the corporate office to a new business as a result of expertise and support provided and not as a result of substantial changes in assets, capital structure, or management.

Restructuring Advantage

The intervention of the corporate office in a new business that substantially changes the assets,

capital structure, and/or management, including selling off parts of the business, changing the

management, reducing payroll and unnecessary sources of expenses, changing strategies, and

infusing the new business with new technologies, processes, and reward systems.

Asset restructuring

Involves the sale of unproductive assets, or even whole lines of businesses, that are peripheral.

Capital restructuring

Involves changing the debt-equity mix, or the mix between different classes of debt or equity.

Management Restructuring

typically involves changes in the composition of the top management team, organizational structure,

and reporting relationships.

Portfolio Management

A method of a) assessing the competitive position of a portfolio of businesses within a corporation, b)

suggesting strategic alternatives for each business, and c) to identify priorities for the allocation of

resources across the businesses.

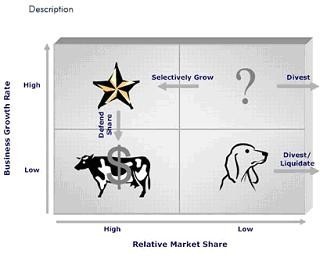

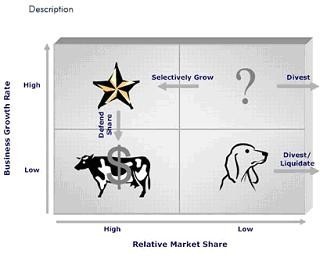

The Boston Consulting Group’s (BCG) growth/share matrix is among the best known portfolio models, which assists firms in achieving a balanced portfolio of businesses. Each of the four quadrants of the grid has different implications for the strategic business units (SBUs) that fall into that category :1) Stars;2) Question Marks;3) Cash Cows;4) Dogs.

1) Stars: are SBUs competing in high-growth industries with relatively high market shares. These firms have long-term growth potential and should continue to receive substantial investment funding;

2) Question Marks: are SBUs competing in high-growth industries but having relatively weak market shares. Resources should be invested in them to enhance their competitive positions;

3) Cash Cows: are SBUs with high market shares in low-growth industries. These unites have limited long-run potential but represent a source of current cash flows to fund investments in “stars” and “question marks”;

4) Dogs: are SBUs with weak market shares in low-growth industries. Because they have weakpositions & limited potential, most analysts recommend divesting them.

In using portfolio strategy approaches, a corporation tries to create synergies and shareholder value in a number of ways:

1) Portfolio analysis provides a snapshot of the businesses in a corporation’s portfolio;

2) The expertise and analytical resources in the corporate office provide guidance in determining what firms may be attractive (or unattractive) acquisitions;

3) The corporate office is able to provide financial resources to the business units on favorable terms that reflect the corporation’s overall ability to raise funds;

4) The corporate office can provide high-quality review and coaching for the individual businesses;

5) Portfolio analysis provides a basis for developing strategic goals and reward/evaluation systems for business managers.

Limitations of Portfolio Models:

1) They are overly simplistic; consisting of only two dimensions (growth and market share);

2) The view each business as separate, ignoring potential synergies across businesses;

3) The process may become overly largely mechanical, minimizing the potential value of managers’ judgment and experience;

4) The reliance on strict rules for resource allocation across SBUs can be detrimental to a firm’s long-term viability;

5) The imagery (e.g. cash cows, dogs) while colorful, may lead to troublesome and overly simplistic prescriptions.

6.3 The Means to Achieve Diversification

a. Mergers and Acquisitions

Merger: the Combining of two or more firms into one new legal identity.

Acquisition: the incorporation of one firm into another through purchase.

Motives and Benefits

Mergers and acquisitions can:

- Be a means of obtaining valuable resources that can help an organization expand its product offerings and services;

- Provide the opportunity for firms to attain the three bases of synergy that were addressed earlier in the chapter – leveraging core competencies, sharing activities, and building market power;

- Lead to consolidation within an industry and can force other players to merge.

Potential Limitations:

- The takeover premium that is paid for an acquisition is very high;

- Competing firms often can imitate any advantages realized or copy synergies that result from the M&A;

- Managers’ credibility and ego can sometimes get in the way of sound business decisions;

- There can be many cultural issues that may doom the intended benefits from M&A endeavors.

Divestment

The exit of a business from a firm’s portfolio (also known as the other side of “the M&A coin”).

b. Strategic Alliance and Joint Venture

Strategic Alliance: a cooperative relationship between two or more firms.

Joint venture: new entities formed within a strategic alliance in which two or more firms, the parents, contribute equity to form the new legal entity.

Motives and Benefits:

- Often a company that has a successful product or service wants to introduce it into a new market;

- Strategic alliances (or joint ventures) often enable firms to pool capital, value-creating activities or facilities in order to reduce costs;

- Strategic alliances also may be used to build jointly on the technological expertise of two or more companies in order to develop products technologically beyond the capability of the companies acting independently.

Potential Downsides and Limitations:

- Without the proper partner, a firm should never consider undertaking an alliance, even for the best of reasons;

- Each partner should bring the desired complementary strengths to the partnership;

- The partners must be compatible and willing to trust each other.

Internal Development

Firms that engage in internal development are able to capture the value created by their own innovative activities without having to “share the wealth” with alliance partners or face the difficulties associated with combining activities across the value chains of several companies or merging corporate cultures. However, internal development can be very time consuming; thus, firms may forfeit the benefits of speed that growth through mergers or acquisitions provide.

6.4 How Managerial Motives Can Erode Value Creation

- Growth for growth’s sake: there are huge incentives for executives to increase the size of their firm, and many of these are hardly consistent with increasing shareholder wealth;

- Egotism: sometimes, when pride is at stake, CEOs might go to great lengths to win;

- Antitakeover Tactics: like greenmail, golden parachute or poison pills are common to prevent hostile takeovers, but they raise ethical considerations.

We live in a highly interconnected global community where many of the best opportunities for growth and profitability lie beyond the boundaries of a company’s home country. Along with the opportunities, of course, there are many risks associated with diversification into global markets.

7.1 Factors Affecting a Nation’s Competitiveness

The Diamond of National Advantage

1) Factor conditions: a nation’s position in factors of production (such as land, labor, and capital);

2) Demand conditions: the nature of home-market demand for the industry’s product or service;

3) Related and supporting industries: the presence, absence, and quality in the nation of supplier

industries and other related industries that supply services, support, or technology to firms in

the industry value chain;

4) Firm strategy, Structure, and rivalry: the conditions in the nation governing how companies are

created, organized, and managed, as well as the nature of domestic rivalry.

7.2 International Expansion: A Company’s Motives

There are many motivations for a company to pursue international expansion:

1) The most obvious one is to increase the size of potential markets for a form’s products and services;

2) Expanding a form’s global presence also automatically increases its scale of operations, providing it with a larger revenue and asset base. Such an increase potentially enables a form to attain economies of scale;

3) Another advantage would be reducing the costs or research and development as well as operation costs;

4) International expansion can also extend the life cycle of a product that is in its maturity stage in a firm’s home country but that has greater demand potential elsewhere;

5) Finally, international expansion can enable a firm to optimize the physical location for every activity in its value chain. Optimizing the location for every activity in the value chain can yield one or more of three strategic advantages: performance enhancement, cost reduction, and risk reduction.

7.3 Potential Risks of International Expansion

1) Political Risk: potential threat to a firm’s operations in a country due to ineffectiveness of the domestic political system;

2) Economic Risk: potential threat to a firm’s operations in a county due to economic policies and conditions, including property rights laws and enforcement of those laws;

3) Currency Risk: potential threat to a firm’s operations in a country due to fluctuations in the local currency’s exchange rate;

4) Management Risk: potential threat to a form’s operations in a country due to the problems that managers have making decisions in the context of foreign markets.

Global Dispersion of Value Chains:

- Outsourcing: using other firms to perform value-creating activities that were previously performed in-house;

- Offshoring: shifting a value-creating activity from a domestic location to a foreign location.

7.4 Achieving Competitive Advantage in Global Markets

Strategies that favor global products and brands:

- Should standardize all of a firm’s products for all of their worldwide markets;

- Should reduce a firm’s overall costs by spreading investments over a larger market;

- Are based on three assumptions:

- Customer needs and interests worldwide are becoming more homogeneous;

- People (worldwide) prefer lower prices at high quality;

- Economies of scale in production and marketing can be achieved through supplying global markets.

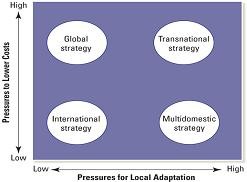

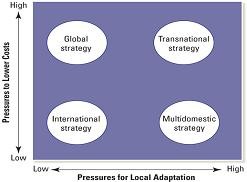

The two opposing pressures result in four different basic strategies that companies can use to compete in the global marketplace : International Strategy, Global Strategy, Multidomestic Strategy, Transnational Strategy.

1) International Strategy: is based on diffusions and adaptation of the parent company’s knowledge and expertise to foreign markets. Country units are allowed to make some minor adaptations to products and ideas coming from the head office, but they have far less independence and autonomy compared to multidomestic companies.

Strengths:

- Leverage and diffusion of a parent firm’s knowledge and core competencies;

- Lower costs because of less need to tailor products and services.

Limitations:

- Limited ability to adapt to local markets;

- Inability to take advantage of new ideas and innovations occurring in local markets.

2) Global Strategy: is based on the emphasis on lowering costs. Competitive strategy is centralized and controlled to a large extent by the corporate office. Since the primary emphasis is on controlling costs, the corporate office strives to achieve a strong level of coordination and integration across the various businesses.

Strengths:

- Strong integration across various businesses;

- Standardization leads to higher economies of scale, which lowers costs;

- Helps create uniform standards of quality throughout the world.

Limitations:

- Limited ability to adapt to local markets;

- Concentration of activities may increase dependence on a single facility;

- Single locations may lead to higher tariffs and transportation costs.

3) Multidomestic Strategy: is based on the emphasis on differentiating its products and service offerings to adapt to local markets. Decisions evolving from a multidomestic strategy tend to be decentralized to permit the firm to tailor its products and respond rapidly to changes in demand.

Strengths:

- Ability to adapt products and services to local market conditions;

- Ability to detect potential opportunities for attractive niches in a given market, enhancing value.

Limitations:

- Decreased ability to realize cost savings through scale economies;

- Greater difficulty in transferring knowledge across countries;

- May lead to “overadaptation” as conditions change.

4) Transnational Strategy: strives to optimize the trade-offs associated with efficiency, local adaption, and learning. It seeks efficiency not for its own sage, but as a means to achieve global competitiveness. It recognizes the importance of local responsiveness but as a toll for flexibility in international operations.

Strengths:

- Ability to attain economies of scale;

- Ability to adapt to local markets;

- Ability to locate activities in optimal locations;

- Ability to increase knowledge flows and learning.

Limitations:

- Unique challenges in determining optimal locations of activities to ensure cost and quality;

- Unique managerial challenges in fostering knowledge transfer.

7.5 Entry Modes of International Expansion

A firm has many options available to it when it decides to expand into international markets (see the figure). Given the challenges associated with such entry, many firms start on a small scale and then increase their level of investment and risk as they gain greater experience with the overseas market in question.

1) Exporting: producing goods in one country to sell to residents of another country.

Benefits: since firms start from scratch in sales and distribution when they enter new markets

and they recognize that they cannot master local business practices, meet regulatory requirements,

hire and manage local personnel, they minimize their risk by hiring local distributors and investing

very little in the undertaking. The firm gives up control of strategic marketing decisions to the local

partners to benefit from their valuable expertise and knowledge of their own markets

Risks and Limitations: in a study of 250 instances in which multinational firms used local distributors

o implement their exporting entry strategy, the results were dismal, mainly because of the lack of a

collaborative, win-win relationship.

2) Licensing: a contractual arrangement in which a company receives a royalty or fee in exchange for the right to use its trademark, patent, trade secret, or other valuable intellectual.

Benefits: in international markets, an advantage of licensing is that the firm granting a license incurs

little risk, since it does not have to invest any significant resources into the country itself.

Risks and Limitations: the licensor gives up control of its product and forgoes potential revenues

and profits. Furthermore, the licensee may eventually become so familiar with the patent and trade

secrets that it may become a competitor (e.g. by modifying the product).

3) Franchising: a contractual arrangement in which a company receives a royalty or fee in exchange for the right to use its intellectual property; it usually involves a longer time period than licensing and includes other factors, such as monitoring of operations, training, and advertising.

Benefits: franchising has the advantage of limiting the risk exposure that a firm has in overseas

markets. At the same time, the firm is able to expand the revenue base of the company.

Risks and Limitation: with franchising, the multinational firm receives only a portion of the revenues,

in the form of franchise fees.

4) Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures: joint ventures and strategic alliances differ in that joint ventures entail the creation of a third-party legal entity, whereas strategic alliances do not. In addition, strategic alliances focus on smaller initiatives than joint ventures.

Benefits: these strategies have been effective in helping firms increase revenues and reduce costs

as well as enhance learning and diffuse technologies. These partnerships enable firms to share the

risks as well as the potential revenues and profits. Entering into partnerships with host country firms

can provide very useful information on local market tastes, competitive conditions, etc.

Risks and Limitations: to minimize risks there needs to be a clearly defined strategy that is strongly

supported by the organizations that are party to the partnership. Closely allied to the first issue, there

must be a clear understanding of capabilities and resources that will be central to the partnership.

Third, trust is a vital element. Fourth, cultural issues that can potentially lead to conflict and

dysfunctional behaviors need to be addressed.

5) Wholly Owned Subsidiary: a business in which a multinational company owns 100 percent of the stock. There are two ways a firm can establish a wholly owned subsidiary:

1) To acquire an existing company in the home country;

2) To develop a totally new operation (often referred to as a “Greenfield venture”).

Benefits: it can yield the highest returns and it provides the multinational company with the greatest

degree of control of all activities, including manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and technology

development.

Risks and Limitations: wholly owned subsidiaries are typically the most expensive and risky of the

various entry modes. The risks associated with doing business in a new country can be lessened by

hiring local talent.

8.1 Entrepreneurship

The creation of new value by an existing organization or new venture that involves the assumption of risk. For an entrepreneurial venture to create new value, three factors must be present: opportunity recognition, resources to pursue the opportunity and an entrepreneur/entrepreneurial team willing and able to undertake the opportunity. New value can be created in start-up ventures, major corporations, family-owned businesses, non-profit organizations, established institutions etc.

1) Opportunity recognition: the process of discovering and evaluating changes in the business environment, such as a new technology, sociocultural trends, or shifts in consumer demand, that can be exploited.

Discovery phase:

- Period when you first become aware of a new business concept;

- May be spontaneous and unexpected;

- May occur as the result of deliberate search for new venture projects or creative solutions to business problems.

Opportunity formation phase:

- Evaluating an opportunity (can it be developed into a full-fledged new venture?);

- Talk to potential target customers;

- Discuss it with production or logistics managers;

- Conduct feasibility analysis (Market potential, Product concept testing, Focus groups, Trial runs with end users).

For an opportunity to be viable, it needs to have four qualities:

1) Attractive: there must be market demand for the new product or service;

2) Achievable: the opportunity must be practical and physically possible;

3) Durable: it must be attractive long enough for the development and deployment to be successful;

4) Value creating: it must be potentially profitable.

2) Entrepreneurial Resources: hand-in-hand with the importance of markets (and marketing) to new-venture creation, entrepreneurial firms must also have financing. In general, financial resources will take one of two forms:

a. Equity: funds invested in ownership shares such as stock. The value of equity funding increases or decreases depending on firm performance. To obtain it usually requires that business founders give up some ownership and troll of the business (e.g. personal savings, investments by family and friends, private investors, venture capital or public stock offerings);

b. Debt: borrowed funds such as interest-bearing loans. In general, debt funding must be repaid regardless of firm performance. To obtain it usually requires that some business or personal assets are used as collateral (e.g. bank loans, credit cards, loans by family and friends, mortgaged property, supplier financing or public financing).

Clearly, financial resources are essential for entrepreneurial ventures. But other types of resources are also vitally important.

Human Capital

The most important asset an entrepreneurial firm can have is strong and skilled management. Managers need to have a strong base of experience and extensive domain knowledge, as well as an

ability to make rapid decisions and change direction as shifting circumstances may require.

Social Capital

New ventures founded by entrepreneurs who have extensive social contacts are more likely to succeed than are ventures started without the support of a social network. Even though a venture may be new, if the founders have contacts who will vouch for them, they gain exposure and build legitimacy faster.

Government Resources

In the United States, the federal government provides support for entrepreneurial firms in two key arenas – financing and government contracting. The Small Business Administration (SBA) has several loan guarantee programs designed to support the growth and development of entrepreneurial firms. The SBA also offers training, counseling, and support services through its local offices and Small Business Development Centers.

3) Entrepreneurial Leadership: whether a venture is launched by an individual entrepreneur or an

entrepreneurial team, effective leadership is needed. Three characteristics of effective

leadership are:

a. Vision (may be an entrepreneur’s most important asset);

b. Dedication and drive (are reflected in hard work);

c. Commitment to excellence (requires entrepreneurs to develop a commitment to knowing the customer, providing quality goods and services, paying attention to details, and continuously learning).

8.2 Entrepreneurial Strategy

As suggested earlier, one of the most challenging aspects of launching a new venture is finding a way to begin doing business that generates cash flow, builds credibility, attracts good employees, and overcomes the liability of newness.

Pioneering new entry

A firm's entry into an industry with a radical new product or highly innovative service that changes the way business is conducted.

Imitate new entry

A firm's entry into an industry with products or services that capitalize on proven market successes

and that usually has a strong marketing orientation.

Adaptive new entry

A firm's entry into an industry by offering a product or service that is somewhat new and sufficiently

different to create value for customers by capitalizing on current market trends.

To achieve competitive advantages new ventures can use the following generic strategies:

1) Overall cost leadership: one of the ways entrepreneurial firms achieve success is by doing more with less. Thus, under the right circumstances, a low-cost leader strategy is a viable alternative for some new ventures. New ventures often have simple organizational structures that make decision making both easier and faster. The smaller size also helps young firms change more quickly when upgrades in technology or feedback from the marketplace indicate that improvements are needed.

2) Differentiation: both pioneering and adaptive entry strategies involve some degree of differentiation. That is, the new entry is based on being able to offer a differentiated value proposition. However, several factors make it more difficult for new ventures to be successful as differentiators (e.g. strategy is expensive to enact, differentiation is often associated with strong brand identity, differentiation successes are sometimes built on superior innovation or use of technology).

3) Focus: focus strategies are often associated with small businesses because there is a natural fit between the narrow scope of the strategy and the small size of the firm. Since most start-ups enter industries that are mature, young firms can often succeed best by finding a market niche where they can get a foothold and make small advances that erode the position of existing competitors.

Although each of the three strategies holds promise, and pitfalls, for new ventures, firms that can make unique combinations of the generic approaches may have the greatest chances of success.

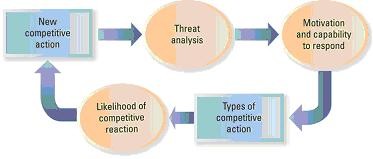

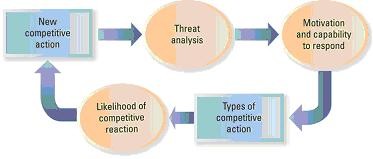

8.3 Competitive Dynamics

New entry into markets, whether by start-ups or by incumbent firms, nearly always threatens existing competitors. As a result, a competitive dynamic – action and response – begins among the firms competing for the same customers in a given marketplace.

New Competitive Action

Companies launch new competitive actions, because of the desire to strengthen financial outcomes, capture some of the extraordinary profits that industry leaders enjoy, and grow the business. Examples for improving competitive position and consolidating gains in preparation for another attack are:

- Devastate rivals’ profit: not all business segments generate the same level of profits for a company;

- Sanctuaries: through focused attacks on a rival’s most profitable segments, a company can generate maximum leverage with relatively smaller-scale attacks. Recognize, however, that companies closely guard the information needed to determine just what their profit sanctuaries are;

- Plagiarize with pride: just because a close competitor comes up with an idea first does not mean it cannot be successfully imitated. Second movers, in fact, can see how customers respond, make improvements, and launch a better version without all the market development costs. Successful imitation is harder than it may appear and requires the imitating firm its keep its ego in check;

- Deceive the competition: a good gambit sends the competition off in the wrong direction. This may cause the rivals to miss strategic shifts, spend money pursuing dead ends, or slow their responses. Any of these outcomes support the deceiving firms’ competitive advantage. Companies must be sure to not cross ethical lines during these actions;

- Unleash massive and overwhelming force: while many hardball strategies are subtle and indirect, this one is not. This is a full-frontal attack where a firm commits significant resources to a major campaign to weaken rivals’ positions in certain markets. Firms must be sure they have the mass and stamina required to win before they declare war against a rival.

- Raise competitors’ costs: if a company has superior insight into the complex cost and profit structure of the industry, it can compete in a way that steers its rivals into relatively higher cost/lower profit arenas. This strategy uses deception to make the rivals think they are winning, when in fact they are not. Again, companies using this strategy must be confident that they understand the industry better than their rivals.

Types of Competitive Actions

Once an organization determines whether it is willing and able to launch a competitive action, it must determine what type of action is appropriate:

- Strategic actions: major commitments of distinctive and specific resources to strategic initiatives (e.g. entering new markets, new product introductions, changing production capacity, mergers / alliances);

- Tactical actions: refinements or extensions of strategies usually involving minor resource commitments (e.g. price cutting / or increases, product / service enhancements, increased marketing efforts, new distribution channels).

Before launching a given strategy, however, assessing the likely response of competitors is a vital

step.

Likelihood of Competitive Reaction

Evaluating potential competitive reactions helps companies plan for future counterattacks. How a competitor is likely to respond will depend on three factors:

- Market dependence: if a company has a high concentration of its business in a particular industry, it has more at stake because it must depend on that industry’s market for its sales;

- Competitor’s resources: for example, a small firm may be unable to mount a serious attack due to lack of resources. As a result, it is more likely to react to tactical actions such as incentive pricing or enhanced service offerings because they are less costly to attack than large-scale strategic actions;

- Actor’s reputation: whether a company should respond to a competitive challenge will also depend on who launched the attack against it.

Choosing Not to React: Forbearance and Co-opetition

In many circumstances the best reaction is no reaction at all. This is known as forbearance – refraining from reacting at all as well as holding back from initiating an attack. Related to forbearance is the concept of “co-opetition”. This term suggests that companies often benefit most from a combination of competing and co-operating. Close competitors that differentiate themselves in the eyes of consumers may work together behind the scenes to achieve industrywide efficiencies.

Despite the potential benefits of co-opetition, companies need to guard against co-operating to such a great extent that their actions are perceived as collusion, a practice that has legal ramifications in the United States.

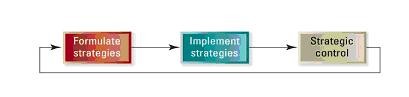

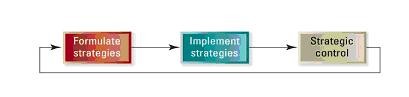

9.1 Two types of control systems

1) Traditional approach to strategic control: a sequential method of organizational control in which (1) strategies are formulated and top management set goals, (2) strategies are implemented, and (3) performance is measured against the predetermined goal set. Control is based on a feedback loop from performance measurement to strategy formulation (see the figure below).

Most appropriate:

- When environment is stable and relatively simple;

- Goals and objectives can be measured with certainty;

- Little need for complex measures of performance.

Limitations:

- Process typically involves lenghty time lags, often tied to the annual planning cycle;

- Little or no action taken to revise strategies, goals and objectives until the end of the time period.

2) Contemporary approach to strategic control: this approach suggests continually monitoring the environments (internal and external) as well as identifying trends and events that signal the need to revise strategies, goals and objectives. Relationships between strategy formulation implementation and control are highly interactive.

Informational control

A method or organizational control in which a firm gathers and analyzes information from the internal and external environment in order to obtain the best fit between the organization’s goals and strategies and the strategic environment (‘doing the right things’).

Behavioral control